Brain cells that regulate whole-body metabolism and energy intake die without a key enzyme

The enzyme NAMPT is crucial for the survival of neurons that help to makes us eat when we are hungry discover scientists from the University of Copenhagen. The discovery suggests that imbalances in levels of the enzyme could affect our ability to regulate our energy needs, and play a role in the development of obesity and type 2 diabetes.

The body’s energy needs are regulated by the brain, leading scientists to question whether it might hold answers for treating obesity and diabetes. Scientists at the University of Copenhagen have discovered that neurons in the hypothalamus of the mouse brain that regulates food intake and energy balance, die without the enzyme NAMPT.

The enzyme is needed to produce the molecule NAD, which is made from Vitamin B3 and which all cells need for a variety of cellular functions. The findings suggest that imbalances in levels of NAD in this area of the brain may play a role in the development of obesity and type 2 diabetes.

“It is crucial that cells properly balance levels of NAD, and either producing too little or consuming too much can affect their ability to function. An imbalance in these processes in the brain may result in metabolic diseases such as obesity and diabetes,” says Associate Professor Jonas Treebak from the Novo Nordisk Foundation Center for Basic Metabolic Research (CBMR) at the University of Copenhagen.

Dysregulation of NAMPT may affect energy regulation in the brain

In research published last year in Acta Physiologica, his team demonstrated that mice were unable to register the hunger hormone ghrelin if their brains were treated to limit the activity of NAMPT. The gut releases ghrelin in response to fasting, and normally stimulates the appetite, but in these mice they failed to eat more after being held in a fasted state.

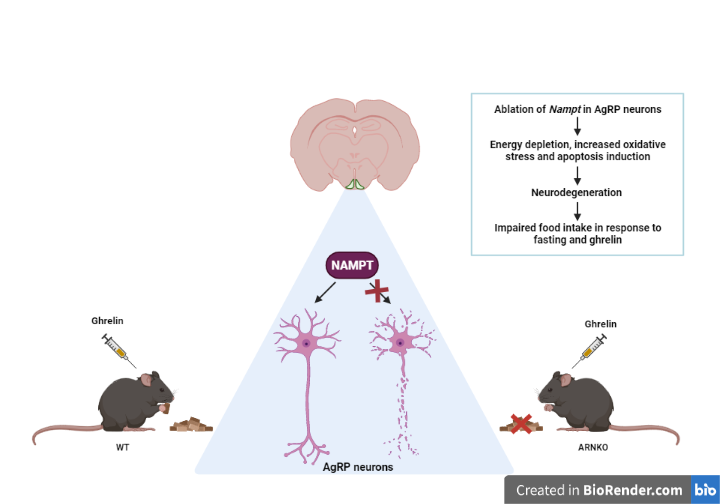

In the latest study, published in The FASEB Journal they targeted the so-called AgRP neurons in the brain, which are known to stimulate the appetite when ghrelin is released after a period of fasting. They bred mice that did not produce NAMPT in AgRP neurons, and studied their development from embryos through adulthood.

Like the mice in the earlier research, they found that these mice also did not increase their food intake in response to fasting or ghrelin. They also discovered that without NAMPT, NAD levels were depleted and the AgRP neurons gradually started to die after the mice reached weaning age and transitioned from lactating to eating solid foods. These findings suggest that NAMPT is vital for the survival of AgRP neurons and suggests that a dysregulation of NAMPT could affect the brain’s ability to properly regulate its energy needs.

“Our research highlights the crucial importance of NAMPT for the survival of AgRP neurons. It is not surprising that the feeding behavior of mice was affected if depleting levels of NAMPT, which lowers NAD levels, leads to neurodegeneration. This dysregulation of NAD in the area of the hypothalamus that regulates feeding, may be why some people overeat, or don’t feel full after eating,” says PhD student Anna Skab Hassing.

Read the full article in FASEB: 'Ablation of Nampt in AgRP neurons leads to neurodegeneration and impairs fasting- and ghrelin-mediated food intake'

Contact:

Associate Professor Jonas Thue Treebak

Novo Nordisk Foundation Center for Basic Metabolic Research

University of Copenhagen

jttreebak@sund.ku.dk