Scientists search for the signal that stops us from gaining weight

The body might have an undiscovered defense against gaining too much weight – a signal that tells our brain to dampen our appetite. This is a theory being developed by researchers at the Novo Nordisk Foundation Center for Basic Metabolic Research (CBMR). Finding this signal could be a landmark moment in understanding body weight biology, which could accelerate the development of therapies that could help to tackle the global obesity epidemic

We don’t eat the same amount of food each day, and some days we are more active than others. Still, most adults will find that their bodyweight remains very stable throughout their life. Our brain is responsible for this incredible balancing act – making sure we eat enough food to cover our energy needs, but not so much that we continuously gain weight.

Scientists have a good understanding of how our brain makes us hungry to stop us from losing too much weight. But what’s less well understood is how the brain reduces our appetite when it senses that we have enough energy stored in our body.

Why do some people stay lean?

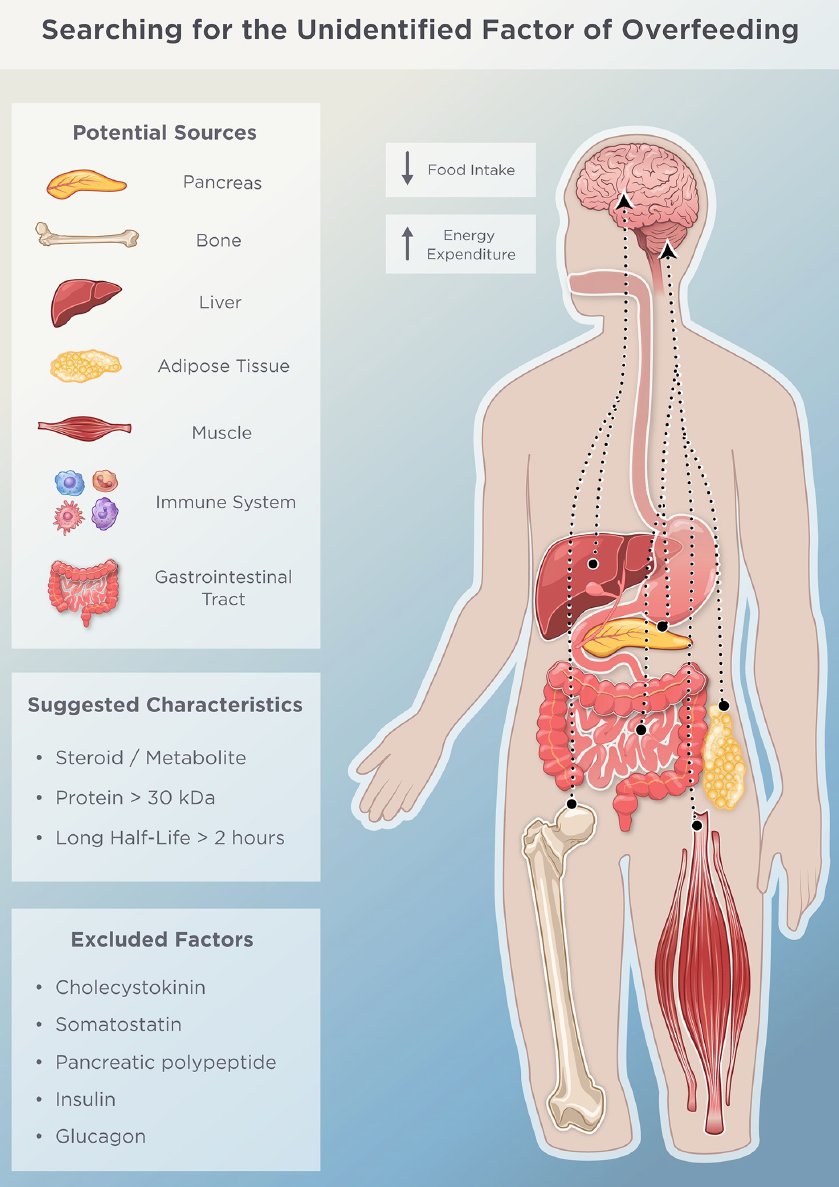

Researchers from the Novo Nordisk Foundation Center for Basic Metabolic Research (CBMR) at the University of Copenhagen are trying to answer this question. And they have a theory – an undiscovered chemical signal that is released by our organs in our body, which tells our brain to dampen our appetite.

“There is a lot of evidence that there is a signal that defends our body against weight gain, which we have yet to discover,” says Associate Professor Christoffer Clemmensen. “If we can discover this signal, it will give us a better understanding of how the brain keeps the body in an energy balance, which could lead to new treatments for obesity.”

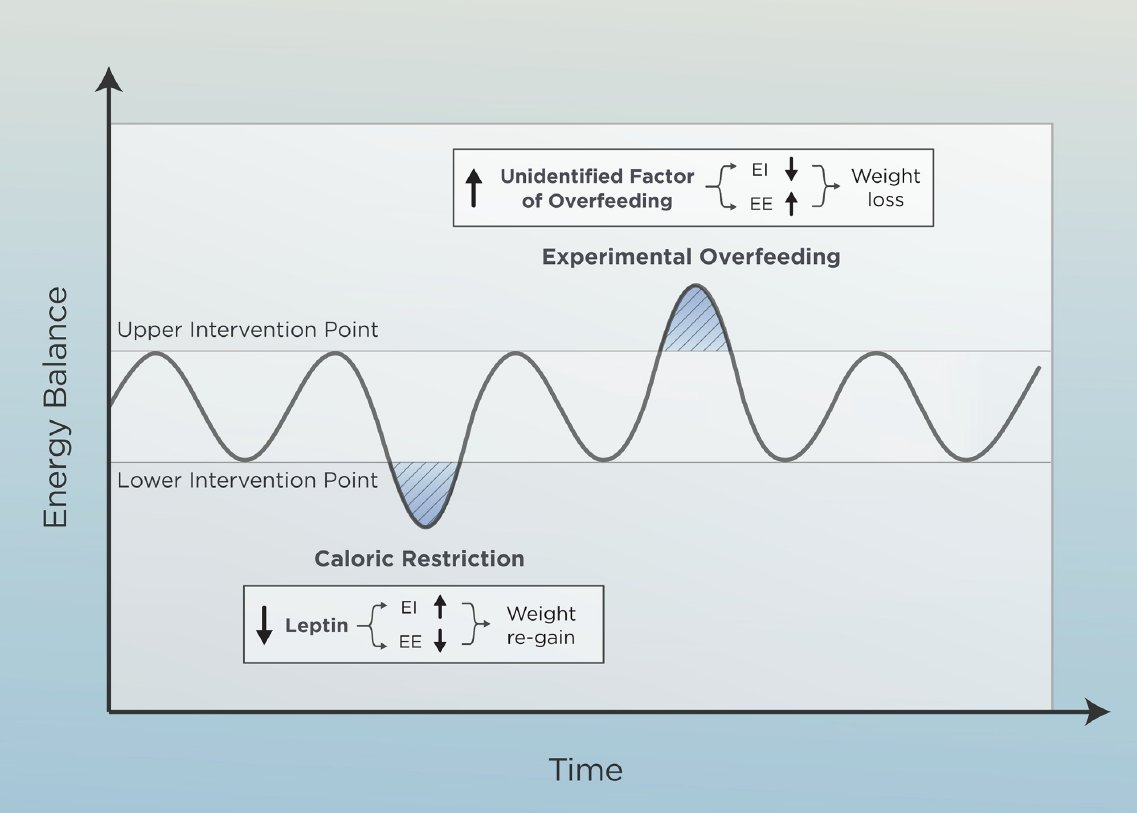

Clemmensen and his colleagues have presented their theory in the journal PLOS Biology, in which they argue that our brains try to keep our body weight between an upper and lower boundary. When our weight drops too low, our hunger increases, which drives us to eat more. And when our weight passes above a certain threshold, another mechanism kicks in to dampen our appetite and lower our weight.

“Whether it’s eating 5000 calories in one sitting, or doubling your food intake over a long period, it’s very difficult to force someone to overeat if they aren’t hungry. We think this is because in the process your upper weight boundary is threatened. And we are convinced that this biological threat ignites the release of an unknown signal that tells our brain that we are exceeding our individual upper boundary,” Clemmensen explains.

The evolution of weight gain

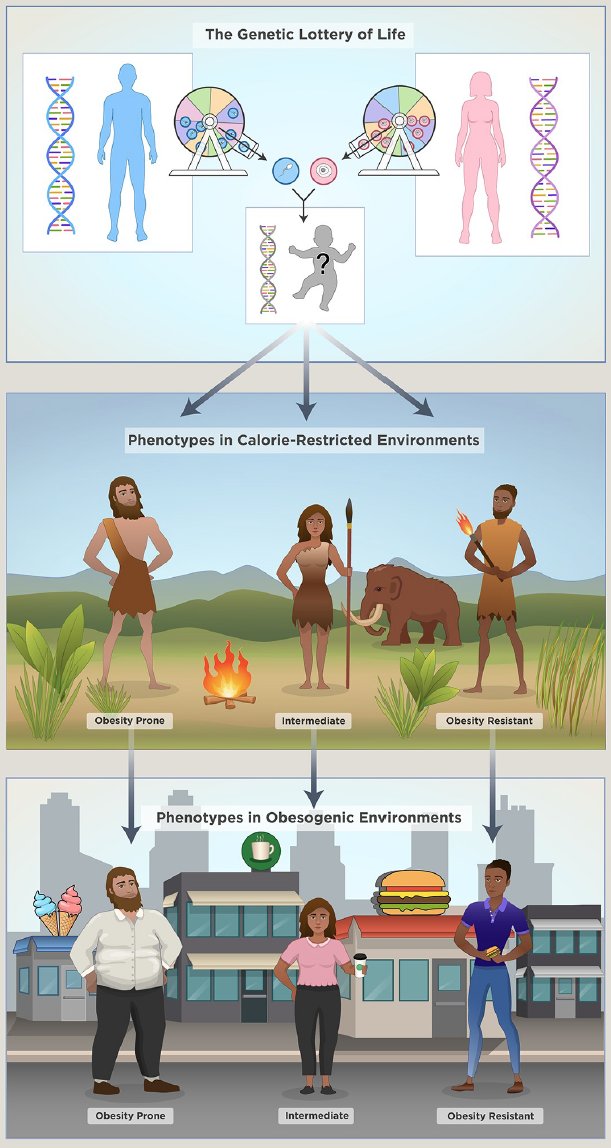

So why is it that there are very few underweight people compared to overweight people? The researchers argue that evolutionary forces have kept the lower boundary stable – if it were too low, people would not have enough fat mass to survive and pass on their genes.

By contrast, the upper boundary might has shifted upwards during human evolution, explains PhD student Jens Lund.

"Our ancestors have been preyed upon for millions of years. Weighing too much in these periods lowered one's chance of successfully escaping attacks from large predators and evolution therefore selected against excessive body weight. However, once early humans became top-predators themselves, this defense against obesity was no longer needed. As a result, obesity susceptibility has randomly spread from generation to generation. This provides one explanation for why some of us today are prone to weight gain while others are resistant."

The threat of cheap, tasty and calorie-rich food

But there is an additional explanation for why increasing numbers of people around the world are living with obesity. Until recently, most people had a hard time getting hold of enough calories to satisfy their energy requirements, let alone overeat. But we now live in a very different world with constant access to tasty and energy rich food.

According to Clemmensen, there is strong evidence to suggest that this ‘obesogenic’ food environment causes some people to overeat – a phenomenon called hedonic overeating. And if you combine a predisposition to hedonic eating, with an insensitive defence mechanism to weight gain, you end up with a dangerous biological cocktail that puts you at high risk of developing obesity.

“Maybe up to two-thirds of the population has a very high upper boundary, which means that the mechanisms are not being engaged to powerfully counteract the weight gain,” says Clemmensen. And that difference might be determined by genetics, argues PhD student Jens Lund.

“Most people think they are largely in control of their own body weight, but within a population between 40-70 percent of the variability in body weight is determined by our genes. Fighting our fattening food environment is simply much easier for some than for others.”

New studies of overfeeding are needed to find the signal

Scientists already understand how a number of different hormones help the brain to regulate the body’s weight. Leptin, for example, plays a role in protecting against weight loss by telling the brain that our fat depots are becoming dangerously low. This signal is partially responsible for why it is so hard to lose weight through dieting.

However, no known hormone has been show to play a role in protecting us against weight gain – despite the evidence that it must exist.

“We believe there is another signal that hasn’t been discovered because it isn’t frequently found in sufficiently high levels in most subjects enrolled in clinical studies. So we need to do more studies in a so-called overfed state to trigger the biological response that counteracts overeating,” says Clemmensen.

Finding this signal could be the starting point for developing drugs that can tackle the global obesity epidemic. More than 600 million people around the world now live with obesity, but few effective methods of treating the disease exist. Although lifestyle and behavioural modifications are first choice of treatment, studies show that these types of interventions are not always enough. Most people would benefit from additional help in the form of an effective drug.

Finding this signal could be the starting point for developing drugs that can tackle the global obesity epidemic. More than 600 million people around the world now live with obesity, but few effective methods of treating the disease exist. Although lifestyle and behavioural modifications are first choice of treatment, studies show that these types of interventions are not always enough. Most people would benefit from additional help in the form of an effective drug.

Clemmensen and his colleagues are hopeful that this signal can be discovered with the technological resources that are available at CBMR.

“We finally possess the methodologies that are required to identify chemical satiety signals, which are circulating in our blood but have not yet been discovered,” says Clemmensen.

Read the full article in PLOS Biology: 'The unidentified hormonal defence against weight gain'